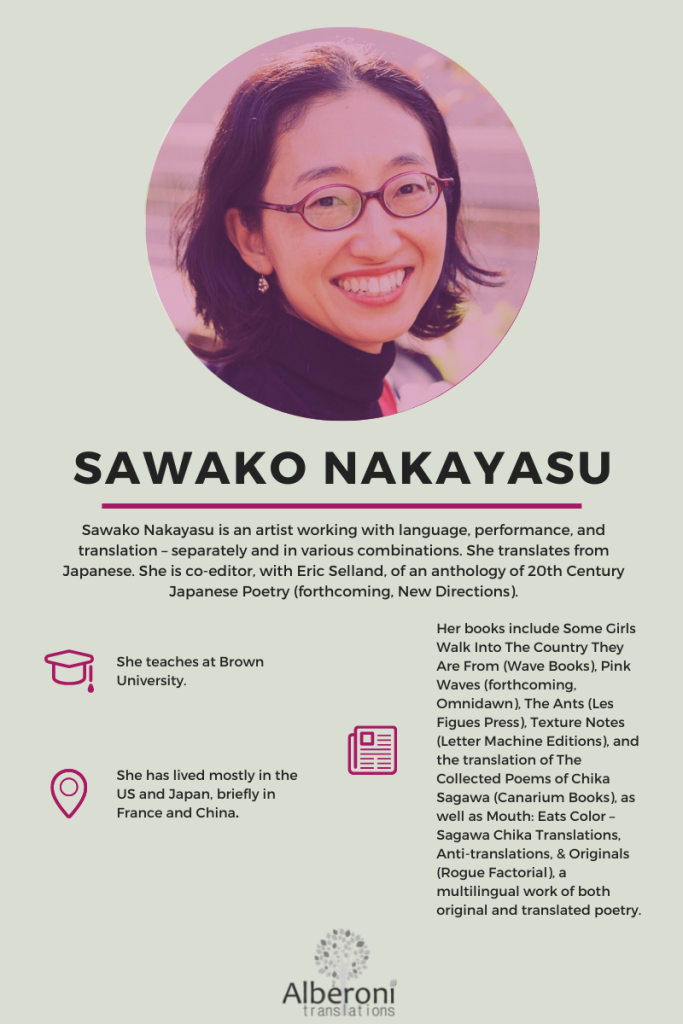

Sawako Nakayasy was nominated by Rosmarie Waldrop.

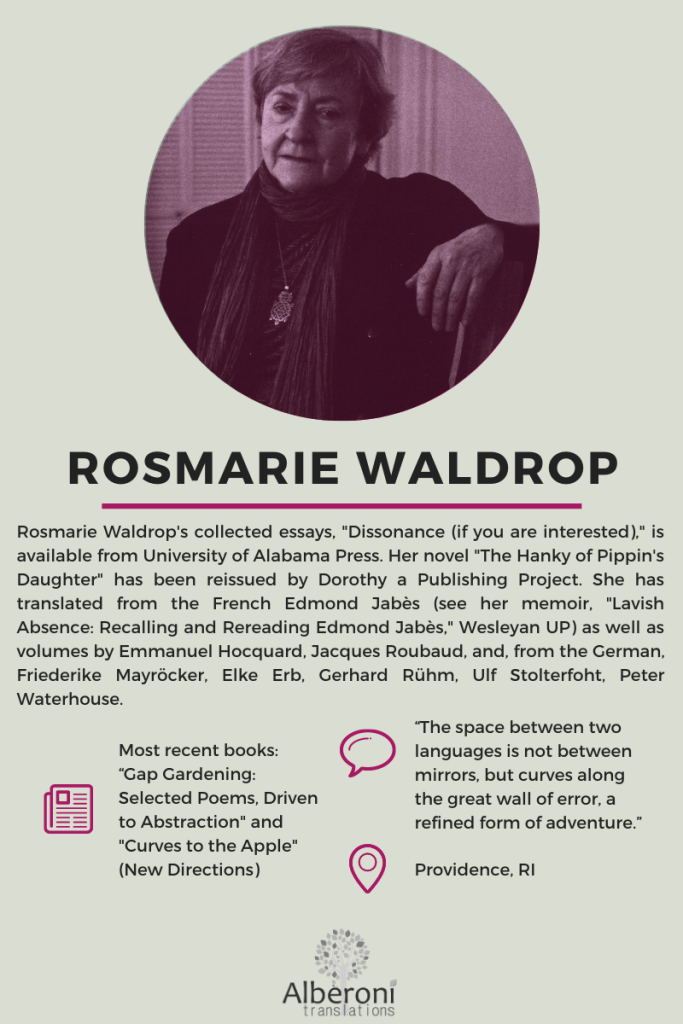

1. Let me start by saying that I absolutely loved this interview you gave to Lindsey Webb on Asymptote Journal, so most of the first three questions will be based on parts of it. I’d like to start with a comparison Forrest Gander made at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference of you and Rosmarie Waldrop, our previous interviewee, in which he described you as “the Rosmarie Waldrop of Japan.” Just like Waldrop, you are a poet-translator “explicitly invested in disrupting a largely male avant-garde” (Webb). Could you tell us a little more about this?

Thank you so much, Caroline! (Or is it Carol?) It’s of course a great honor to be called the “Rosmarie Waldrop of Japan,” but it’s also quite a bit to live up to – I continue to admire Rosmarie endlessly for the range, depth, and breadth of her work. And Forrest Gander has always been incredibly supportive of my work, and of women writers in general (in every country, I might add). Regarding feminism: it’s not that I only translate women, but my own sensibility affects the decisions that I make. And if that happens to loosen the grip of the male avant-garde, all the better. There’s still plenty more work to do on many fronts.

The excellent Japanese women poets I’ve translated include Kawata Ayane, Kyongmi Park (who is zainichi – Korean in Japan), Hirata Toshiko, Ito Hiromi, Minashita Kiriu – and also the modernist poet Sagawa Chika, who was basically unknown at the time I found her work. A “minor poet,” or “everybody’s favorite unknown poet,” depending on who you asked. I think that latter description, “everybody’s favorite unknown poet,” says so much about the mismatch between fame (the state of being known) and the quality of the work.

Often we work with the assumption that we are supposed to translate the “best” – from any given language or culture. And in that sense, I’m not so different. I simply found Sagawa’s poetry astounding, and wanted to share it with others. My esteem of her work did not correspond with that of the Japanese literary establishment, but I was young, brash, and utterly convinced that I had found a truly wonderful poet – it never bothered me to be questioned on why I was translating such a “minor” poet. For this, I want to thank Keith Waldrop for imparting an “art for art’s sake” ethos, early on. He simply was not the careerist type, and didn’t care a lick about “professionalizing” his students. And so I arrived at translation with the mindset of making art. “Make it better in the translation,” Keith said – which is an empowering message for emerging translators.

My translation of Sagawa Chika received a good amount of recognition, got acquired and republished by Modern Library, a Penguin/Random House imprint, alongside major canonical writers. Now her work is widely distributed in English and some of it has been translated from English into other languages like Chilean Spanish, Galician, and Arabic. Sagawa’s poems, written in the 1920s and 1930s, are avant-garde and ahead of her time, and quite singular – almost like the Emily Dickinson of Japan, though Sagawa was less isolated. And now she will be the subject of a scholarly, digital publication project that focuses exclusively on her work, so her reach continues to grow.

2. Yes, Carol is perfectly fine. When talking about your experimental translation project Mouth: Eats Color—Sagawa Chika Translations, Anti-Translations, & Originals, Webb says you give “the reader privileged access to the mind of the translator as it crosses languages, cultures, and (in Sagawa Chika’s case) time.” How is that so?

If you sit down and try to capture what moves through a translator’s mind as they translate a poem… it’s possible that a “true” transcription of such a thing could be quite fascinating or banal or hilarious, depending. In the case of Mouth: Eats Color, I might say that this is the case, but taking place over a long span of time. I spent about ten years translating Sagawa’s Collected, and I wrote Mouth: Eats Color during a summer within that time period. I was feeling constrained about certain conventions of translation (basic ones, like making the translation as similar as possible to the text one is translating, or of creating one translation per poem) – but there were aspects of Sagawa’s poetry that made me question the basic principles and customs of translation altogether. Her work really comes out of Japanese modernity – the major shifts in culture, society, technology, philosophy, and exposure to new modes of art – as well as an aesthetic Modernism that is fused with her very unique style and sensibility. And then, when you start considering the poems of James Joyce, Harry Crosby, and Mina Loy that she herself had translated into Japanese, alongside the poems of hers which were clearly influenced by the various poems she had been translating, there is a fascinating web of influence and innovation.

So it’s natural, in a way, that she has influenced my thinking about translation. I knew that there was more to explore beyond whatever I was doing in the conventional translation of her work, even though I was absolutely still also committed to translating her Collected in the conventional mode. As a translation, Mouth: Eats Color is more performative – I was trying to enter the space and context and energy of what it must have been like to be Sagawa Chika in the 1920s and 1930s, having moved from Hokkaido to Tokyo, into an interdisciplinary artistic and literary milieu that was abuzz with new ideas and translations and poetics, with the language itself evolving and changing rapidly, with new printing technologies suddenly available and accessible, and with her having such a singular mind, a distinct personal style that came through with such clarity. Lately I’ve been working on finishing the 20th century Japanese experimental poetry anthology (co-edited with Eric Selland), so I’ve enjoyed spending more time thinking about the context in which she wrote. And then I think: why might happen if Sagawa Chika was alive today?

3. I absolutely loved this quote of yours: “Translating is such a different task from writing in your own language—it involves a lot of patience to be willing to work it and work it and work it until the tunnel opens up. There are all these issues that you’re trying to satisfy all at once. It’s very painful. My own writing is contingent on circumstances surrounding my physical space and mind. I’m not an athlete about writing. So to translate I have to build up a lot of muscles. If I haven’t been translating a lot, I feel the weakness—it really feels muscular.” Do you believe a translation is ever finished?

“Never finished, only abandoned” – it’s a well-worn quote, but personally I think “abandoned” is a bit harsh. I prefer to think of it as “handed over” – to the reader, for example, who completes the work by reading, interpreting, or receiving it. That said, whenever you hand something over for production into publication, it’s an implicit statement that it is “finished” to some degree at least, so it’s a little disingenuous to claim otherwise. Might as well admit we participate in the capitalist commodity culture that this is – or rather, I think it’s important to acknowledge it as one choice among many, and that there are other choices to be made. I self-published Mouth: Eats Color because I did not want to subject it to external approval, as well as external conditions and parameters – the only way I could have full control of it was to produce it myself, and that turned out to be wonderfully empowering. Print-on-demand technology allowed me to self-publish it with very little money. I remember doing a class visit once, and a student asked, “how did you get a book like this published?” – and I was happy to say that I didn’t.

But your question referred to work, labor, and muscle. I can add that part of what let me feel free to engage Sagawa’s work so intimately (and differently) was because I was also doing the normal, “respectable” thing in translating her Collected in a conventional manner, and that Mouth: Eats Color wasn’t some lazy, irresponsible copout – it was faster, and there is certainly a sense of infinite possibility in it, but I was not averse to doing the more constrained work of a regular translation. Both projects come from a place of deepest respect. In fact, I hope that people read the two books together. Then you would have a much fuller picture of “Sawako Nakayasu translating Sagawa Chika.”

Also, my computer is littered with translations that literally never got finished – false starts, weak attempts, abandoning in the sense of giving up. Multiple times in my life I have tried to translate my own poems into Japanese, which I was completely unable to do – and so I embraced the notion of the unfinished, failed-attempt translation and included some of them in my new book, Some Girls Walk Into The Country They Are From, which opened up new doors along that translation-writing continuum. That in turn has led me to Pink Waves, which lands on a very different spot on that same continuum.

Some of these explorations come from my background in music and dance improvisation, which involves a very different process. You practice, rehearse, train. Like an athlete. Or, you walk on the wall, like Trisha Brown. The work is time-bound and restricted to that moment, which leaves no room for the kind of revising and editing that I would do for a conventional translation. Mouth: Eats Color is also performative in that I wrote during a particular moment of my life – I had a very specific, Cinderella-like amount of time to “be a writer/translator” (one month), after which point I had to return to being an overworked mom of a newborn baby teaching eight classes a week. As someone once said to me: you can do it all, but you can’t do it all at the same time.

4. As a Japanese translator who lives abroad, how do you keep in touch with your culture and language, and polish your language and translation skills?

I spent a lot of time moving back and forth between Japan and the US. But for me it’s more about the books than about speaking and being in the place. When you’re first learning a language, immersion seems critical, but I can be “immersed” in a Japanese book no matter where I am.

5. How did you get into translation?

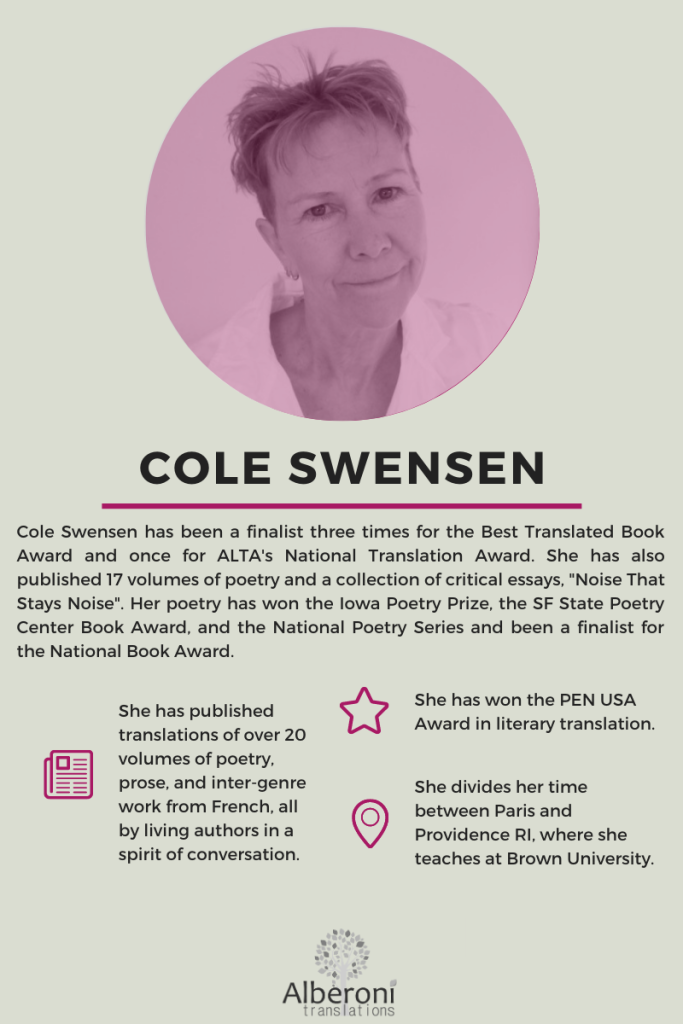

Power of suggestion, and circumstance. Keith and Rosmarie Waldrop and Forrest Gander, were tremendous role models. I also happened to move to Japan upon completing my MFA in poetry, and translation was a way for me to learn more about Japanese poetry.

6. What have you been working on during this pandemic and how has it changed your life, both in the personal and professional levels?

I’ve had a challenging pandemic, and am hoping to come out of it wiser and kinder.

7. Now it’s your turn to nominate our next Great Woman in Translation.

Aditi Machado

Imagem fornecida pela autora

Imagem fornecida pela autora Laila Compan é tradutora de espanhol, especialista em legendagem e tradução para dublagem, professora de legendagem, palestrante e idealizadora e criadora de conteúdo do Tradutor Iniciante.

Laila Compan é tradutora de espanhol, especialista em legendagem e tradução para dublagem, professora de legendagem, palestrante e idealizadora e criadora de conteúdo do Tradutor Iniciante. Created by Erick Tonin

Created by Erick Tonin Created with Canva

Created with Canva