Welcome back to our interview series, dear readers!

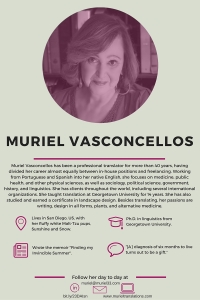

Please meet Muriel Vasconcellos, nominated by Allison Wright, and be as amazed as I were with her life lessons.

1. You are a translator from Portuguese and Spanish to English with more than 40 years of experience in the fields you mention above. I can see where your expertise in linguistics comes from (you hold a Ph.D. in Linguistics from Georgetown University), but what about the rest of your expertise?

Most of it comes from on-the-job experience, learning while doing, with the benefit of excellent coaching during the early years of my career. After working in administration and translating on the side for several years, I landed my first real job as a wordsmith with the Organization of American States in Washington, D.C. I was both an editor and a translator in the Department of Social Affairs, and the documents covered a wide variety of topics that affect developing countries. My supervisor, Betty Robinson, was brilliant and taught me a lot. In addition, during much of my time in that position I was detailed to the Language Services Division, where senior translators reviewed my work and generously shared their wisdom – always tactfully, never in the spirit of showing off.

After six years at the OAS, I applied for a position with the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the World Health Organization’s American regional office, in its Department of Research Development and Coordination. I was responsible for publishing a series of monographs and my work included editing, translating, précis-writing at scientific meetings, and report-writing. My boss, Dr. Maurício Martins da Silva, set aside an hour every morning before work to tutor me in the biomedical sciences. I repaid him by working long hours and on weekends. Dr. Maurício was a born teacher and I owe my understanding of science to him.

2. You also taught translation at Georgetown University for 14 years. How do you think this experience as a translation teacher helped (or still helps) you as a translator?

Teaching translation gave me a whole different perspective on the process. It was the first time I began to analyze the techniques that before I had been using intuitively. I needed to understand what happens in translation in order to empower my students. The tools, formulas, and solutions that I developed for them are constantly in the back of my mind, guiding me in my work.

3. You were the president of the International Association for Machine Translation for two years and founder and president of the Association for Machine Translation in the Americas for six years. You are also the editor of a collection of contributions on the translator workstation and the use of computer aids and full machine translation, entitled “Technology as Translation Strategy”. Besides, during the time you worked at the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization, you introduced machine translation and developed strategies to facilitate post-editing. Can you tell us a bit more about MT from your point of view?

Having been up close and personal with machine translation for 35 years, I have a lot of thoughts on the subject. I have expressed them in more than 50 published articles, most of them posted on my website.

My first exposure to MT was a five-year stint as assistant to the director of the Machine Translation Project at Georgetown, Professor Léon Dostert, when I came to know all the key researchers and other players in the field. I wrote about this experience in an article titled The Georgetown Project and Léon Dostert. It’s fair to say that the Georgetown Project laid the groundwork for extensive use of information-only MT by the United States Government. Since the 1960s, MT has been effective as an information-gathering tool. There’s little doubt that it has revolutionized the gathering of scientific intelligence.

MT has also enabled businesses, starting with Xerox, to launch products in multiple markets simultaneously. Over the years, the Xerox model has been replicated by many large companies.

Other applications, like weather reports in Canada, have been successful largely because the vocabulary and syntax are relatively limited.

PAHO began to develop its own Spanish-English MT system in 1978. The office’s managers had been sold on the naïve idea that medical texts would easily lend themselves to mechanization. I was placed in charge of the program the following year and we quickly realized that we were faced with a wide range of subject matter, various genres, and vastly different writing styles. Even the strictly medical texts covered a large number of specialties. The Spanish-English system (SPANAM), developed in-house by a team of Georgetown-trained computational linguists headed by Marjory León, was the first to become operational in 1980. English-Spanish (ENGSPAN) debuted later. Both of them have turned out to be robust general-purpose systems and they continue to be improved under the direction of Julia Aymerich. There is also a system from Portuguese to English that still needs work. I used SPANAM in-house for 12 years, while at the same time supervising a team of contractors, and I have continued to use it as a contractor myself since 1992.

When it comes to professional translators in the role of posteditors, I would say that not everyone can adjust their style to minimize the effort involved. Many of us find it hard not to change the output; the decision to leave it alone is frustrating in itself, as we always prefer our own style. The process is also stressful because MT does not eliminate the need to look at the source text. The translator has to be thinking of strategies for fixing the target output, more often needed than not, while still carefully following the source, like patting her head and rubbing her tummy at the same time. It’s a demanding skill.

PAHO pays its translators well for their effort. The rate is only slightly lower than the level paid by international organizations for “human” translation, and the office has been able to recruit a strong team of professionals working both in the house and as contractors.

Perhaps my years of experience as an editor have given me a leg up. There are times when I get frustrated and times when I’m grateful that “the machine” has made my work easier. I also do regular translation for many other clients, so I have ample opportunity to compare the two processes, which are very different.

One problem is that my vision has deteriorated; working on-screen is increasingly difficult for me as I get older. At this point in my career, I like nothing better than to read a sentence in the source language and then close my eyes to process it in my head while letting the translation flow through my fingers. This is how I work best and make the fewest mistakes. An added benefit is that the result sounds more natural.

To conclude, I believe that MT postediting can be used to achieve polished, high-quality translations under the following conditions: the posteditors are professional translators in mid-career (I don’t recommend it for beginners); they are open to taking on the task; they have good keyboard skills; and they are adequately compensated. Using MT as an excuse to exploit translators or hiring non-translators as posteditors are unfortunate trends that should be discouraged.

4. According to your own words, you are “passionately interested in Brazil.” I know your late husband was a Brazilian in political exile when you met, back in 1970. Was he the (only) reason for this passion for the country?

My passion for Brazil began when I started to learn Portuguese. I had taken a break from my university education and was studying business Spanish at the Latin American Institute in New York City. My schedule had an empty slot and my advisor suggested that I sign up for Introductory Portuguese. What a life-changer that was! I have been in love with the language and the Brazilian people ever since.

Returning to Washington, I transferred to Georgetown University’s newly established Institute of Languages and Linguistics, where I opted for a double major in Spanish and Portuguese in the bachelor’s degree program. While my graduate major was linguistics, I continued with a double language minor for both the master’s and the Ph.D. At Georgetown, all the courses on Spanish and Portuguese linguistics were taught in the respective languages.

I met my Brazilian husband after I finished my bachelor’s degree and before I went back to graduate school. He was definitely a factor in my decision to resume my studies.

5. You wrote a memoir, Finding My Invincible Summer, published in late 2012, about your experience with breast cancer. In your words, “a diagnosis of six months to live turns out to be a gift”. Why?

First I’d like to mention that my book also covers a key period in my translation career. I wanted to give up editing and become a full-time translator. After my cancer diagnosis prevented that from happening (for insurance reasons), I got involved in machine translation – and the rest, as they say, is history.

On a personal level, having cancer totally changed my approach to life. The experience taught me that our thoughts create our reality and that we have the capacity to channel our thinking in positive and constructive directions that promote health, joy, and abundance. It’s not hard. Our lives are enriched to the extent that we are grateful for what we already have.

6. You wrote that you walked away from conventional treatment and practiced gentle approaches to becoming and staying well. Could you tell us a bit more about these approaches?

The turning point in my healing process was biofeedback. Through exposure to machines that monitored my stress levels, I was able to hear the storm of electric static that came up when I was feeling challenged. I learned that stressful thoughts arouse the fight-or-flight response that draws on our emergency reserves and literally beats up our bodies unless we can break the vicious cycle and return to equilibrium, or what they call homeostasis. The biofeedback trainers showed me evidence that keeping the body constantly on edge through negative thinking was one of the main causes of chronic disease.

The key to breaking the cycle is deep relaxation. People get similar help from meditation, prayer, and sometimes acupuncture (massage is relaxing, but it’s too distracting to achieve deep relaxation). Whatever it takes, the idea is to stop the tapes that buzz in the head and connect with the essence and power of the present moment. In the beginning I listened to guided relaxation tapes for two and three hours a day. Later I purchased a chi-machine, which has supported my daily deep relaxation process for over 20 years.

Over the years I have enhanced this practice with techniques that help to keep me healthy. Physically, they include belly breathing, jaw jiggling, stretching, walking, biking, stair-climbing, and any other activity that I really enjoy. I try to maintain a sugar- and grain-free diet, minimize dairy, and emphasize healthy fats like ghee and coconut, MCT, fish, flaxseed, and olive oils. Mentally, I do visualization and constantly question my thoughts using a technique similar to Byron Katie’s “Is it true that …? Is it really true that …?” I have embraced Chinese medicine and homeopathy and I avoid prescription medicines whenever possible. Finally, perhaps most important, I have surrounded myself with like-minded people.

7. According to Emma Goldsmith, in her review of the book, you managed “to study and work as a translator in seemingly impossible circumstances”. How did you do it?

You aren’t the first person to ask that question! I answered it in a blog. I explained that I didn’t have any distractions back then: no e-mail, no Internet, no social media, no cell phone; no radio or television. I was totally immersed in my work. I thought about it while getting dressed, driving my short commutes to the office and school, eating at my desk, walking the dog, and even soaking in the tub – where I often got my best inspiration.

I certainly couldn’t do it today. My focus is pulled in a thousand different directions by distractions that we didn’t used to have.

8. Now it’s your turn. Who would you like to invite to be our next interviewee in the Greatest Women in Translation series?

If it’s all right with you, I’d like to take this opportunity to recognize the contributions of Deanna Hammond, a past president of the American Translators Association whose strong and wise leadership navigated the ATA through difficult waters. In her day job, she was head of the translation service at the United States Library of Congress for many years. Deanna would be here to tell her own story if her life hadn’t been cut short by pancreatic cancer at the age of 55.

I was deeply touched and amazed by your story, Muriel. A million thanks for accepting Allison’s nomination to be part of our series! It was a great honor to welcome you here and to be able to e-meet you.

Since Muriel’s nomination is no longer living, she will write a tribute to Deanna Hammond, instead of our normal interview. In April, we will be back with the interviews featuring another one of my personal role models (this time a Brazilian one) so we are back on the loop. Stay tuned!

Thank you so much for sharing your professional and personal life story, Muriel Vasconcellos! And I feel really glad for once more being able to appreciate this wonderful work that you do, Caroline Alberoni. Hugs and kisses, Suany Lima

LikeLike

Thank you, Suany!

I’m really glad you enjoy the series, because I do too. I end up e-meeting amazing people. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, Suany. I agree. Caroline is doing a wonderful job.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My job would be nothing if I didn’t have such wonderful and interesting interviewees. 😉

LikeLike

Dear Caroline,

Thank you for this interview and the admirable idea of interviewing our greatest women in translation. All the best

Anita Di Marco

LikeLike

Hi, Anita!

It’s a great pleasure for me. I didn’t expect to love the series as much as I do now.

Thanks a lot for visiting and taking the time to leave such a lovely message! 🙂

All the best

LikeLike

Pingback: Greatest Women in Translation: Deanna Hammond | Carol's Adventures in Translation

Thank you very much Muriel for sharing your journey – a powerful lesson which may encourage many others who are still walking on this way now… I shared it on my page. I need to read this book…

LikeLike

Pingback: Greatest Women in Translation: Muriel Vasconcellos | czopyk